As part of its larger ‘ease of doing business’ goal, the

Centre has decided to incentivise states through rating

the respective environment impact assessment

authorities on the basis of their efficiency in granting

faster green clearance to projects. The move is, however,

severely criticized by the environmentalists who sought

its immediate withdrawal, saying the government’s

decision will reduce environmental law compliance to a

mere formality as the role of such body is to give nod

after detailed scrutiny which takes time The Centre’s

decision to rank states according to the speed at which

they issue environmental clearances is ill judged and

short sighted. It undermines the role of regulatory

oversight in environmental protection by incentivising

state environment impact assessment authorities

(SEIAA) to seek “fewer details” from project developers.

There is no denying that clearance procedures are often

riddled with red tapism. And that environmental protection

must be balanced with developmental priorities. These

are complex tasks that require strengthening of

institutions and making regulatory procedures foolproof.

Experts have rightly pointed out that the ranking exercise

will compromise the SEIAAs’ mandate to assess the

impact of industrial, real estate and mining schemes on

the environment and lead to an unhealthy competition

amongst these agencies to swiftly clear projects without

due diligence. In recent times, the MoEF has laid much

store on speedy clearances of projects. In a statement

issued in December last year, it pointed out that the

average time taken to issue environmental clearances

had reduced from 150 days to 90 days in the past two

years and that the clearance time is as low as 60 days

in some sectors. But the ministry has not clarified if this

reduction in time has improved the level of scrutiny of

projects on critical environmental yardsticks. The MoEF’s

self-congratulatory tone about the rate of approval has

been rightly criticised because it has coincided with

moves to chip away at key environmental regulation. Last

year, for instance, it weakened the public hearing

provision for Environment Impact Assessment (EIA),

extended the deadline for compliance with emission

norms for most thermal power plants from 2022 to 2025

and planned to reduce the ecological protection accorded

to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

At a time when climate change is driving home the

ecological fragility of large parts of India and pollution

and water scarcity are taking a serious toll on the wellbeing

of people in cities, towns, and villages, regulatory

bodies require enabling policies to perform their tasks

with rigour. The grading exercise, instead, reduces them

to clearing houses. The Centre must rethink its move.

More Stories

CM Files Nomination for Hinjili Assembly Seat

Liquors Policy Scam: ED has no material necessitating my arrest, Kejriwal tells SC

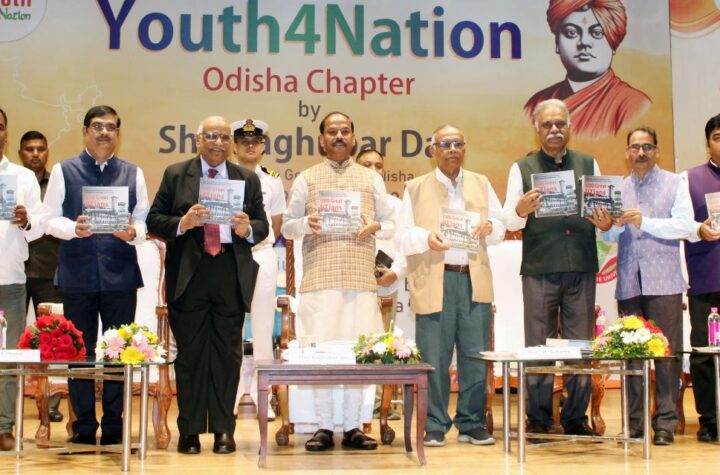

Youth need encouragement & guidance to take India a great heights: Odisha Governor