Soura Chandra Mohapatra The very fact that the constitution of the Indian Republic is the product Utility

of a Historical not of a political revolution but of the research and deliberations of a body of eminent representatives of the people who sought to improve upon the existing system of administration, makes a

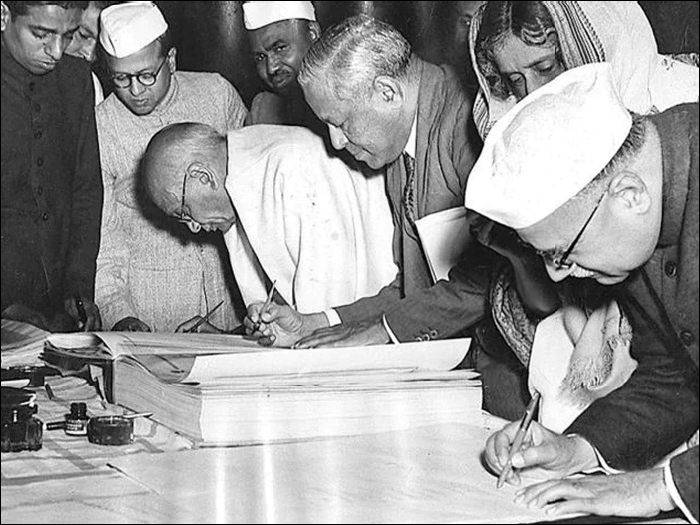

retrospect of the constitutional development indispensable for a proper understanding of this Constitution. Practically the only respect in which the Constitution of 1949 differs from the constitutional documents of the preceding two centuries is that while the latter had been imposed by an imperial power, the Republican Constitution was made by the people themselves, through representatives assembled in

a sovereign Constituent Assembly. That explains the majesty and ethical value of this new instrument and also the significance of those of its provisions which have been engrafted upon the preexisting

system. For our present purposes we need not go beyond the year 1858 when the British Crown

assumed sovereignty over India from the East India Company, and Parliament enacted the first statute for the governance of India under the direct rule of the British Government, the Government of India Act, 1858. This Act serves as the starting point of our survey because it was dominated by the principle of absolute imperial control without any popular participation in the administration of the country,

while the subsequent history up to the making of the Constitution is one of gradual relaxation of imperial control and the evolution of responsible government. By this Act, the powers of the Crown were to be exercised by the Secretary of State for India, assisted by a Council of fifteen members (known as the

Council of India.) The Council was composed exclusively of people from England, some of whom were nominees of the Crown while others were the representatives of the Directors of the East India Co. The Secretary of State who was responsible to the British Parliament, governed India through the Governor-

General, assisted by an Executive Council, which consisted of high officials of the Government. The essential features of the system introduced by the Act of 1858 were centralized. There was no

separation of functions and all the authority for the government of India, civil and military, executive and

legislative was vested in the Governor-General in Council who was responsible to the Secretary of State. The entire machinery of administration was bureaucratic, totally unconcerned about public opinion in India. Relaxation of Central control over the Provinces. As stated already, the Rules made under the Government of India Act, 1919, known as the Devolution Rules, made a separation of the subjects of administration into two categories – Central and Provincial. Broadly speaking, subjects of all India importance were brought under the category ‘Central’, while matters primarily relating to the administration of the provinces were classified as ‘Provincial’. The main features of the governmental system prescribed by the Act of 1935 were as follows – Federation and Provincial Autonomy.

While under all the previous Government of India Acts, the government of India was unitary, the Act of 1935 prescribed a federation taking the Provinces and the Indian States as units. Dyarchy at

the Centre. The executive authority of the Centre was vested in the Governor-General (on behalf of the

Crown), whose functions were divided into two groups. The administration of defense, external affairs,

ecclesiastical affairs, and of tribal areas, was to be made by the Governor-General in his discretion with the help of ‘counselors’, appointed by him. The Legislature. The Central Legislature was bicameral, consisting of the Federal Assembly and the Council of State. According to the adaptations under the Independence Act there was no longer any Executive Council as under the Act of 1919 or counselors as envisaged by the Act of 1935. The Governor General of the Provincial Governor was to act on the advice of a Council

of Ministers having the confidence of the Dominion Legislature or the Provincial Legislature, as the case might be. The sovereignty of the Dominion Legislature was complete and no sanction of the Governor-General would henceforth be required to legislate on any matter and there was to be no

repugnancy by reason of contravention of any Imperial law.

Senior Advocate, Orissa

High Court, Cuttack, Mob:

9437004466

More Stories

LS elections: 4th phase polling records 63 pc turnout

‘Still poor country’: India going to become third largest economy in world

Viksit Bharat, Viksit Odisha: PM Appeals to State People to Vote for BJP