With temperatures at all-time high in 2023, 2024 will be pivotal in reducing emissions, without compromising developmental needs.At COP 21 in Paris eight years ago, countries agreed to “hold global temperature increase to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial efforts and strive to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels”. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events after the Paris Pact led to an unwritten concord on the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit as the defence line against climate change.Paris Pact, COP 21 in Paris, climate change, hottest year, global temperature increase, pre-industrial efforts, frequency of extreme weather events, indian express newsIn 2023, the world came perilously close to this threshold. On average, till November, global temperatures rose by 1.46 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.In 2023, the world came perilously close to this threshold. On average, till November, global temperatures rose by 1.46 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Every month since June was the hottest such month on record, and in November, two days were even warmer than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. The World Meteorological Organisation’s (WMO) provisional State of the Global Climate Report confirms that 2023 is the warmest year on record. The WMO has forecast that the planet will get hotter in 2024.”The warming El Niño event, which emerged during the Northern Hemisphere spring of 2023 and developed rapidly during summer, is likely to further fuel the heat in 2024 because El Niño typically has the greatest impact on global temperatures after it peaks,” the report says.The jury is out on whether climate change has reached a point of no return. But what is clear is that the next seven years will be pivotal in reducing emissions. On the positive side, the International Energy Agency predicts that more than 35 per cent of the world’s electricity will be generated from renewables in 2025. The biggest challenge, however, is generating electricity when the sun isn’t shining or the wind is not blowing.Experts agree on the need for technologies that can cost-optimally store RE anywhere from half a day to a week, even months. At the COP21 in Glasgow, two years ago, countries agreed to set up a Long Duration Energy Storage (LDES) Council to facilitate the commercialisation of technologies – many of them are at the pilot stage – that can stock up RE. However, a market for such solutions is still in the works and most LDES solutions are not cost competitive yet. Scientists agree that along with reducing GHG emissions, the imperative for policymakers should be to build people’s resilience against inclement weather. Such measures could include building sea walls, improving weather alert systems, overhauling urban drainage systems, installing irrigation systems to combat water scarcity or making crop choices suited to the changed climate. As the planet gets hotter, the challenge will be to address vulnerabilities without compromising on people’s developmental needs and lifting large sections out of poverty.

Exclusive

Breaking News

CM Files Nomination for Hinjili Assembly Seat

CM Files Nomination for Hinjili Assembly Seat

Liquors Policy Scam: ED has no material necessitating my arrest, Kejriwal tells SC

Liquors Policy Scam: ED has no material necessitating my arrest, Kejriwal tells SC

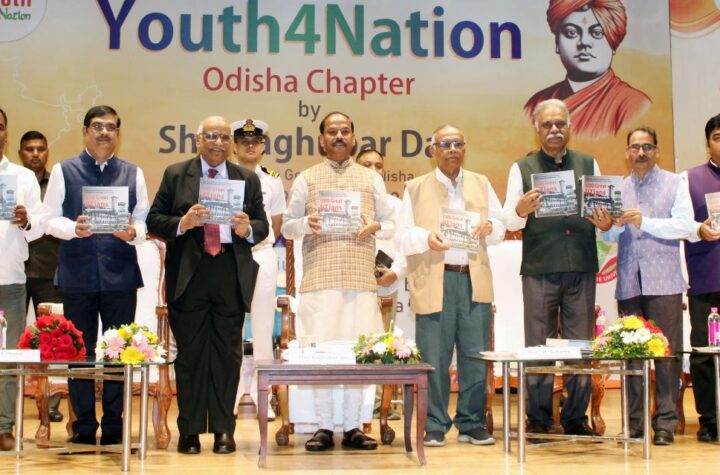

Youth need encouragement & guidance to take India a great heights: Odisha Governor

Youth need encouragement & guidance to take India a great heights: Odisha Governor

26% with criminal cases and 46% crorepatis in third phase

26% with criminal cases and 46% crorepatis in third phase

Columbia University aakes back Deadline set for Protesters to Leave Campus

Columbia University aakes back Deadline set for Protesters to Leave Campus

More Stories

CM Files Nomination for Hinjili Assembly Seat

Liquors Policy Scam: ED has no material necessitating my arrest, Kejriwal tells SC

Youth need encouragement & guidance to take India a great heights: Odisha Governor