At a plant nestled along a highway 20 miles north of Boston, hundreds of Pfizer Inc. workers are gearing up to produce millions of doses of a new vaccine that looks more and more like the next phase of fighting Covid-19.

Work on the project started the day after Thanksgiving at the 70-acre facility in Andover, Massachusetts, just as the World Health Organization designated a new coronavirus strain, omicron, a variant of concern. The goal of the effort: make a booster shot customized against the highly mutated virus in less than 100 days.

Nobody yet knows how widely omicron will spread, how serious its infections will be or even whether the new shots will be necessary. Top White House medical adviser Anthony Fauci has said that reports on severity have so far been “encouraging.” But if laboratory data rolling in from around the world are reliable, the strain is better able to sidestep existing vaccines than any to date.

Of 43 US omicron infections analyzed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, four-fifths were in fully vaccinated people, although almost all the cases were relatively mild. UK health officials expect omicron to overtake delta as the dominant strain there within days.

Researchers are alarmed by some 30 mutations in omicron’s spike, the protein that facilitates coronavirus’s entry to cells. Changes in its appearance make it harder for antibodies to find and destroy the variant. That’s prompted Pfizer, its partner BioNTech SE and their messenger RNA rival Moderna Inc. to start crash efforts to target it directly.

“It was the list of mutations we never wanted to see,” said Moderna President Stephen Hoge, who heads the company’s scientific operations. The vaccine maker, whose mRNA factory stands just 40 miles from Pfizer’s, started working on omicron the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, and meetings ran straight through the holiday. Many employees “had their Thanksgivings ruined” by omicron, Hoge said.

Early lab data suggest that three doses of existing mRNA vaccines protect against omicron. What’s less clear is how long that protection lasts, since Covid antibodies have been seen to wane over time. Pfizer hopes to have the first realworld effectiveness data about how its existing vaccine fares against the variant before the end of the year.

While the companies are tight-lipped about the details of exactly where they stand, both are bent on a fast response. When news of the variant emerged from South Africa, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla decided almost immediately to begin large-scale manufacturing of an omicron-specific shot. The work ramped up so quickly that Pfizer hasn’t tallied its costs.

“I couldn’t give you the number right now; I’m not even sure we talked about it,” said Mike McDermott, Pfizer’s global supply chain head, who gives Bourla regular updates on progress. It’s very unusual for a drug company to start largescale manufacturing on a product that may not be needed, he said.

The production process at Andover could start any day now, McDermott said. Workers are waiting for company researchers in Chesterfield, Missouri, to finalize and deliver a master cell line containing a genetic sequence that will be used in the targeted vaccine.

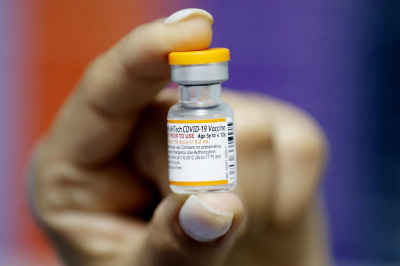

Pfizer’s Andover plant, acquired in 2009 in the $68 billion purchase of vaccine maker Wyeth, specializes in biologic products. For the Covid vaccine, it performs two early steps: producing large quantities of a DNA template for the vaccine from the cell line, and then converting that into the mRNA that forms the core of the vaccine.

The mRNA will be sent to another Pfizer facility in Kalamazoo, Michigan. That facility makes the lipid nanoparticles that coat the mRNA and protect it from enzymes in the body that degrade it. Kalamazoo also has vaccine vial-filling operations.

South of Boston, Moderna’s Norwood, Massachusetts facility has clean-room suites for making mRNA and the lipid nanoparticles that coat the fragile genetic material. Formerly owned by Polaroid, the factory is the vaccine maker’s first and has been rapidly scaling up since the pandemic began.

In 2020, it took Moderna 42 days to produce batches of its original Covid vaccine and 63 days to start human trials with government researchers. With omicron, “our goal is to hit a timeline like that for sure” Hoge, the Moderna president, said.

One reason that both Pfizer and Moderna can move quickly with omicron is that they have the honed the process with both the original vaccines as well as variant vaccines for beta and delta strains the companies produced earlier this year. While the delta and beta variant vaccines may not be needed, it provided a dry run for omicron.

Even after the vials of vaccine are filled and finished, uncertainties loom, starting with what human trials regulators will require, if any. The FDA’s current guidance, which the agency reiterated in an email, calls for immunogenicity trials to compare the human immune response to virus variants induced by the modified vaccine against the response to the authorized vaccine.

But Pfizer research head Mikael Dolsten says the company is exploring whether, in an emergency, it could obtain clearance without the omicronspecific trials. The agency may allow the drugmakers to submit human data from other variantspecific vaccines that show its approach is likely to be successful.

The FDA declined to comment on confidential discussions with vaccine developers.” It said it encourages them to reach out early and often to discuss clinical data needed for new vaccines to help fight Covid.

Should fresh trials of immune response to the booster be required, they would likely involve a few hundred people and take a couple months to complete, Moderna’s Hoge said. “Ultimately, the FDA has to tell us what they want,” he said.

Another question is how quickly omicron expands outside of South Africa. The strain appeared at a time when the country’s caseload was quite low — there wasn’t that much competition from other variants. In a best-case scenario, the new strain might be outspread by delta in most countries and gradually fade away.

In the meantime, though, the drugmakers can’t bank on that possibility. Pfizer plans to have the new doses ready by February or early March, Dolsten said.

More Stories

Modi will come with hope in 2024: PM

IPL: For Bumrah every ball wicket-taking delivery

J&K to get statehood, assembly elections not far: PM